With our radars, more than ever on the climate agenda, I’ve started to think about what more I could be doing at home about energy use, in particular, the way I heat my home. Recently I’ve become aware of local heat networks that are popping up to support rural areas rather than the district heat networks we usually hear about in urban areas. As someone that relies upon LPG to heat my home as well as a data geek, I’m interested in both the application of this technology and the data that supports the feasibility of these schemes in rural areas.

The implementation of these and larger schemes in the UK has been a bit patchy, to say the least, and where homes are already connected to one you can find horror stories of people that have been without hot water and heating for months on end in the depths of winter as well as happier tales that clearly show both financial and environmental benefits.

The Scandinavians have been quietly getting on with district heat networks for some time and are pretty good at it. For example, over 60% of homes in Demark are connected to one of the 450 or so networks in operation. Whilst Denmark is a smaller country with a population density map very different to ours here, I thought that the application and implementation should be replicable to similar geographies in the UK.

After researching what was happening in the UK some more, most of my suspicions were realised when I looked at the data published by Euroheat & Power from 2013 which put UK citizens connected to district heating at 2% compared to the Nordic countries at well over 50% and Iceland at 92%. However, after some further work into more recent statistics for the UK, I was surprised to find out that even by 2020 there were already approximately 17,000 heat networks; 5,500 of them being larger district networks rather than communal ones supplying a handful of properties.

With the UK government’s target to have 17% of homes supplied by district networks by 2030, there’s still quite a jump to move from the 0.5million consumers to the required 8million to meet this target but it seems that we are starting to think that it could provide a significant part of the jigsaw to the future of heating our homes in the future and adopting a low carbon approach.

Clearly, UK government is keen to back this technology as part of the solution too with the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) announcing in 2020 it was making available £40m for the installation of 7 new networks in the UK. Local councils across England including Leeds, Bristol and Enfield and Barking & Dagenham in London are now starting to see the benefits of not only creating new local jobs to support implementation but also being able to provide heat and hot water not only to many of their own property estate buildings but also to local residents. For example, in phase 1 of their project, Leeds City Council has connected about 2,000 residential and commercial premises including the civic and town halls, museum, art gallery and central library and created 400 new jobs in the local economy. Further phases already underway are helping the council meet their net-zero and air quality targets.

Linked to this investment by BEIS it was great to see some good old fashioned data crunching underlying the rationale and analysis which included a geospatial analysis. The paper released in September 2021 by BEIS - Opportunity areas for district heating networks in the UK: National Comprehensive Assessment of the potential for efficient heating and cooling included some great geospatial analysis of demand clusters and intersection matches to appropriate heat sources to estimate the proportion of heat demand that could technically and economically be served by heat networks. The analysis also provided some useful maps of both supply and demand for heat networks and, based on this correlation, identifiable areas where the potential for this technology could be feasible. For councils and infrastructure planners alike it's easy to see how even more granular data with accurate attribution down to the individual property and sub-property can help drive local business cases for investing and adopting heat networks as part of the future of energy supply.

Going back to my initial point that piqued my interest in rural communities - of course, heat networks naturally favour urban areas where there are higher densities of households and building stock where economies of scale can be realised in network infrastructure and connections to sources of waste heat from industry and commerce.

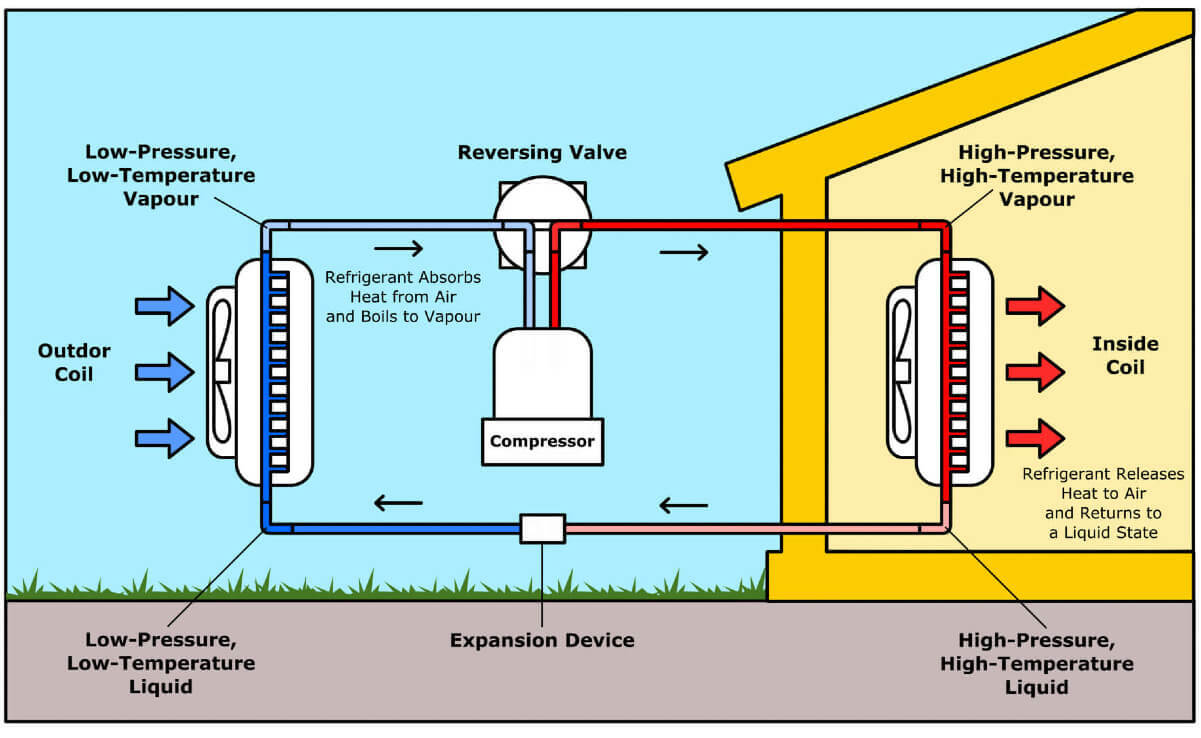

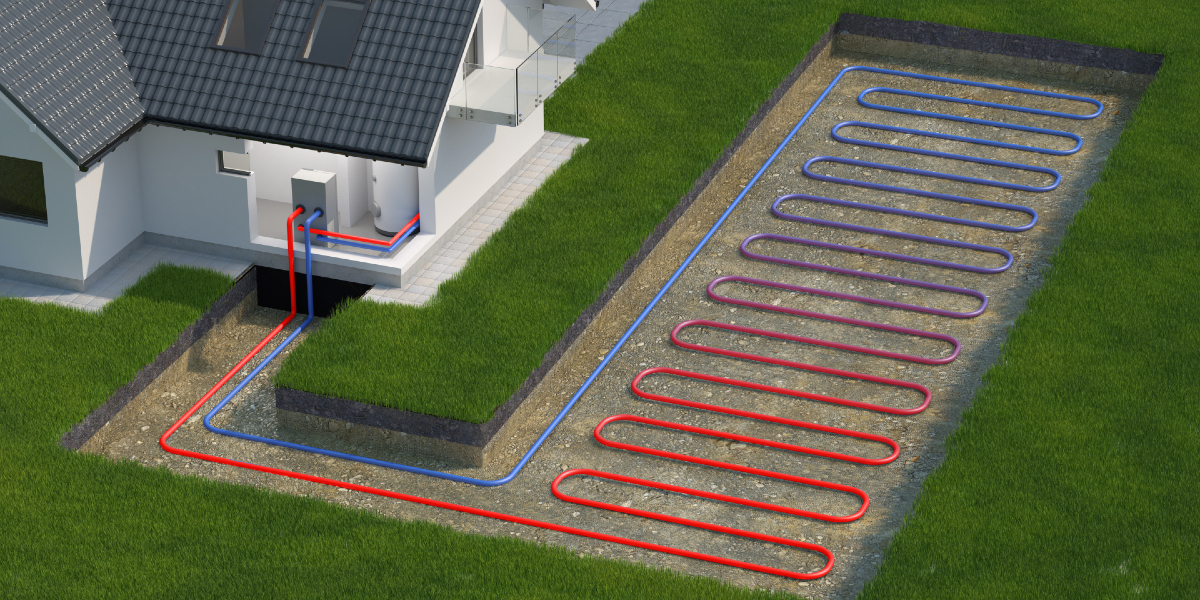

Many rural and remote areas rely on fossil fuels such as oil and LPG and are not connected to national grids and from 2025 UK legislation means that no new building development will be permitted to be connected to the national gas grid. Renewables and heat networks are therefore technologies that will need to lead the way in transitioning existing fossil-based solutions. Low temperature networks using heating sources such as biomass, ground and water heat pumps and anaerobic digesters seem like the most likely options for rural communities so again that granular building and property geospatial data analysis will be important in identifying which clusters of properties in hamlets or villages could form collectives to run off shared ground loops. Hopefully, we’ll start to see great examples like that of Firle village near Lewes.

Greater use of more granular spatial address and street data could also benefit the analysis and identification of the specific properties that are best suited to either a range of different types of sustainable heating and cooling or in some cases limit it down to a single option. For example, the analysis of address attribution about property type, floor area/footprint and whether the property has a garden can rule in and out the different types of heating early on in the design phase of either new builds or as part of retrofitting properties.

Simple online services for owners and occupiers to see if their property is either within a district heating zone or has proximity to one to allow it to be included in energy switching services and similarly services for property owners that want to make the jump into replacing gas or oil boilers with ground or air source heat pumps could also be easily created which quickly provide a viability rating based on an accurate geospatial address location.

Looking into the problems that thousands of people have had with heat networks then much of the bad press seems to be focused on the schemes that are old (but were pioneering in their time) that have suffered from a lack of investment in their maintenance. In addition, the regulation and consumer rights did not seem to have been put in place well enough for those consumers that were already connected to a scheme. District heating schemes in the UK tended not to be regulated and consequently, consumers have had no opportunity to switch energy suppliers and complications in the rights to redress problems with their supply.

The good news is that as of 29 December 2021 the Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (OFGEM) has taken on the responsibility not only to regulate the UK’s heat networks but also to expand their development as part of the UK government's Heat & Buildings Strategy

Knowing that the Unique Property Reference Number (UPRN) is sitting behind OFGEM’s current electricity and gas Faster Switching Programme, as a way of accurately linking meter point data to consumer and business addresses, fills me with greater confidence that geospatial data and analysis is becoming more a necessity for informing and implementing policy and getting us on the road to net-zero at the single household level all the way up through local communities, districts, cities and nationally.

Hopefully with greater access to this type of raw data and consumer focused online solutions we can all start to make our own better informed decision about how to heat our homes.

In theory, these schemes are a no brainer and must be part of the overall strategy that we need to work, on for the net-zero, recycling and sustainable policies to make all our futures a better one.

References:

https://news.leeds.gov.uk/leeds-spotlight/leeds-district-heating-network

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1015585/opps_for_dhnnca_hc.pdf

https://www.energylivenews.com/2020/02/07/government-awards-40m-for-seven-district-heating-networks/

https://mibec.co.uk/district-heating-in-northern-europe-what-can-the-uk-learn/

https://www.boilerguide.co.uk/articles/district-heating-explained